What up, skidmarks? It's Bad Janet.

My annual Halloween costume essay? Featuring hell

Hey there! Welcome to Critic at Play. In addition to writing this newsletter, I serve as the executive editor for sneaker wave magazine, which recently launched Swells, a regular Throwback Thursday column that allows us to reprint stories from the archives. Our first reprint is a Halloween story—MY Halloween story! Check out “the girl who dressed as a turd” to read a true account of my awkward adolescence.

Now, grab yourself a fistful of candy corn and settle in for yet another spooky tale about moral deviation, flawed expectations, and the dubious proposition of life after death.

Disclaimer: this essay will interface heavily with the tv show The Good Place, and it will involve tons of spoilers.

What if you make it to heaven but it turns out heaven sucks? This is essentially the premise of NBC’s original series The Good Place, but with a twist: the reason heaven sucks is because it’s actually hell, and you’re being tortured.

The possibility of heaven sucking has been a long-standing anxiety of mine, since for so many years I believed in a literal heaven, a literal hell, and that the ultimate purpose of my time on earth was to determine in which of those eternal destinations I would end up.

Even without the threat of hell, eternity on its own is a horrifying concept. I mean, you’re telling me it goes on . . . forever?

When I was a kid trying to wrap my head around the alleged endlessness of time, people outside the church seemed more willing to acknowledge the distastefulness of eternity. Christians, however, seemed bound to never admit any weakness or flaw in their belief system and therefore pretended they couldn’t fathom any aspect of eternity that wasn’t to like. Not even, you know, its eternal duration.

This gave a real Emperor’s New Clothes vibe to sermon series about the afterlife. We’re all collectively pretending we really want this thing that we’re not even sure exists—and if it does exist, we’re not completely convinced it’s as great as everyone else wants us to believe? I mean, EVERYTHING we were working toward was so that we could be, like, cosmically compensated with *checks notes* “eternity in heaven praising Jesus on streets of gold”? What are the streets of gold about, anyway? Aren’t we supposed to not be motivated by financial gain? And it’s not like you can take streets to the bank (I mean, besides the streets that you take to get to the bank), so are the glizty pavers purely decorative? Is the gold functional flooring, better for the joints, like some kind of celestial sprung wood? Since gold is metallic, does that make the streets conductive, like heated tiles?

And what about the implicit musical element of heaven? Are there really angels hanging out playing harps, like in all the Precious Moments illustrations? What if I’m a bad singer? Would I be a better singer in heaven? But if heaven changes me, am I really the one there?

Like a boa constrictor winding its body tighter and tighter around its prey, these thoughts would circle around my mind at night and keep me up, breathless and terrified. What if everything I believed was built on a shoddy foundation? Where could I put my trust that wasn’t equally spun from the same source material as all my other beliefs? I didn’t yet know the phrase “turtles all the way down,” but as an evangelical girl in the early twenty-first century, my belief structure was basically crosses all the way down.

To further exacerbate my fears, the Christian media engine pumped out such celestial-centric drivel as the 2014 film, “Heaven is For Real,” based on the book of the same name, about a boy who allegedly visits Heaven and meets Jesus and his rejuvenated great-grandfather (among others) while his corporeal form is on a surgeon’s operating table for an emergency appendectomy. Look, I’m not here to write in depth about that movie or the book; Joelle Kidd has a fantastic chapter about the Christian film industry in her new book, Jesusland, which I highly recommend.

In terms of how Christian culture (as distinct from Christian belief) taught me to think about the afterlife, allow me to foist upon you this 2005 Christian satire song, “Lots of Caucasians.” Some things you should know before you watch the music video:

- Dan Smith, the musical artist, is also behind “Baby Got Book,” a parody of Sir Mix-a-Lot’s iconic hit, “Baby Got Back.” In Baby Got Book, Dan Brown claims: “I like big Bibles and I cannot lie, you Christian brothers can’t deny . . . “ You get the picture. I regret to inform you that I can still rap every word of Baby Got Book to this day.

- “Lots of Caucasians” uses as its source melody the MercyMe song, “I Can Only Imagine,” a praise and worship song originally released in 2001 that remains one of the best-selling and most-played Christian music songs of all time. In 2018, the story behind the song was turned into a Christian film of the same title, directed by the Erwin Brothers. Again, if you want more of a deep dive into Christian film, go get yourself a copy of Jesusland.

- I had not listened to “Lots of Caucasians” in nearly two decades before writing this newsletter, and I do not know what to make of it. In one way, the satirical song mirrors its source material, not explicitly offering answers about the supposed afterlife but asking open-ended questions. But the implication that heaven will be predominantly white really rubs me the wrong way—let the record show that I am not endorsing this song. I just want you to be aware of how confusing it was to try to wrap my ten-, eleven-, twelve-year-old brain around eternity praising Jesus in heaven, dancing (yes, probably off-beat) on streets of gold.

The point I’m trying to make is that my adolescence was infused with an intense but often indirect emphasis on the afterlife, and I didn’t know what to make of it.

For the most part, my strategy for coping with the existential fear of heaven was to not think about it. I believed that it was dangerous, and therefore off-limits, to think thoughts that weren’t doctrinally or denominationally approved.

This willful self-limitation is one of the traits that made me such a good Christian for so long. I did not question figures of authority; I took them at their word. I assumed the inferiority of my own understanding, and I was rewarded for this blind obedience and praised for my faith.

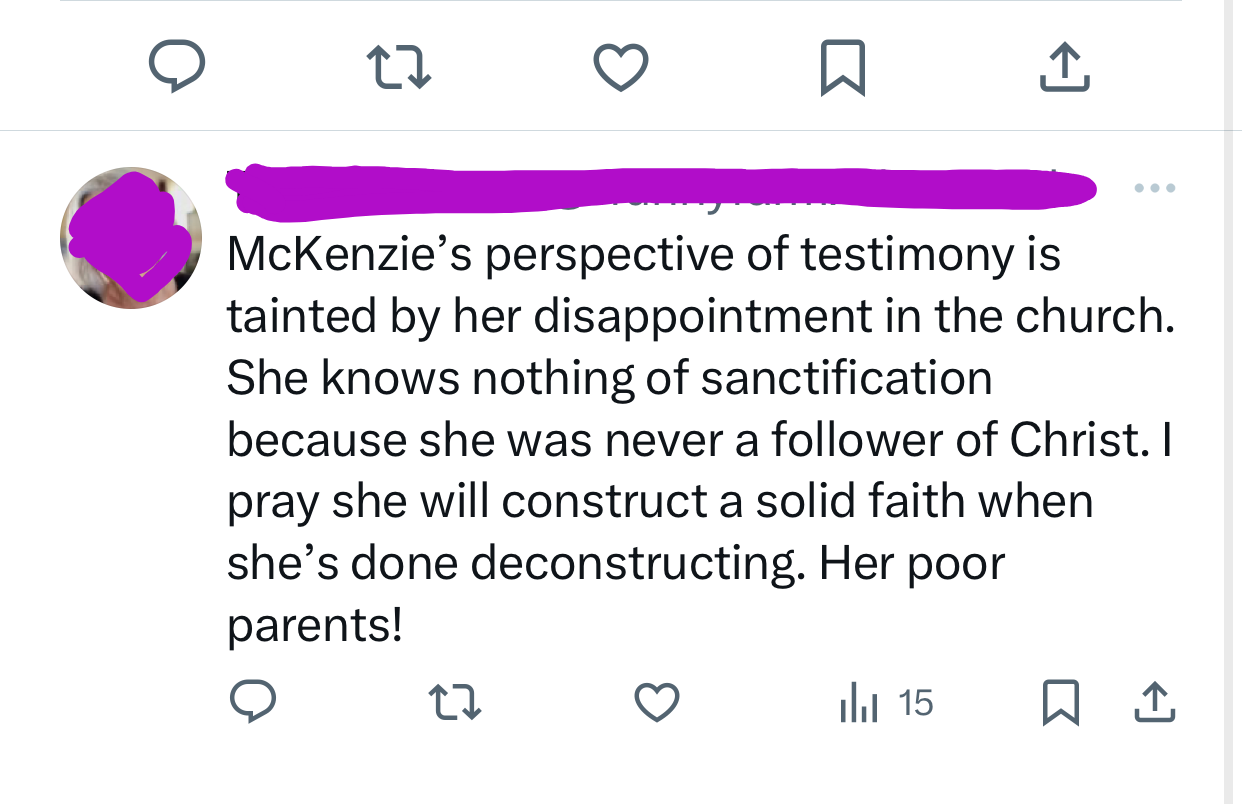

Followers who do what I did are incredibly useful to an authoritarian leader. I was part of the ground corps, the assembly of bodies leveraged to convey force. Other than my obedience, I was dispensable—which is why you see evangelicals target prominent “deconstructors” so viciously.

By the time I got married in my mid-twenties, I hadn’t thought directly about heaven or hell in a long time. Religion exists to help us confront the ultimate questions, which include: how do we cope with the frailty and uncertainty of being human? What do we do with all the existential unknowns? But daily discipline and denominational infighting can insulate us from these core queries. Questions of the afterlife had receded from my regular consideration. Then, in 2020, to while away the long nights of pandemic lockdowns, my partner and I watched The Good Place.

The first thing that struck me as liberating about The Good Place is its willingness—commitment, even—to be wildly imaginative. The show’s creators do not seem to be limited by intellectual fealty to externally imposed ideas. (Pop quiz: where do we even get most of our cultural ideas about heaven and hell? If you answered “the Bible,” you are WRONG. Far more often, our visions of the afterlife are populated with imagery from extrabiblical sources like Dante’s Inferno and Jonathan Edwards’ “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Case in point: remember those harp-strumming Precious Moments angels I mentioned? That’s our cultural image of a “cherub,” derived not from the Bible but from the putto movement in 15th century Italian art and further popularized via the masterworks of the Italian Renaissance. The below video is a great explanation of how we went from the Biblical description of angels to these plump little archers in frescoes.)

The creators of The Good Place go all in developing their own frameworks for heaven and hell—henceforth referred to as the good place and the bad place, respectively. The way to gain entrance to either of these places is based on a complicated point system that totals up the cumulative effect of one’s life on Earth. This system is relayed to our four human protagonists—Eleanor Shellstrop, Chidi Anagonye, Tahani Al-Jamil, and Jason Mendoza—by their non-human collaborators: Michael, a demon firesquid in a skin suit who is fascinated by humans; and Janet, a not-robot/not-girl with access to all known information in the universe.

The Janets—for lo, they are legion—are essentially the engines of the afterlife. They come in many forms: Good Janet, Bad Janet, Neutral Janet, even Disco Janet! Architects like Michael design the afterlife neighborhoods, but the Janets are the ones who make it all run.

Here, I have to include a quick synopsis of the show (I’m trying to minimize spoilers, but this will definitely reveal certain plot twists, so if you haven’t seen the show yet and still intend to come to it tabula rasa, just repost this essay now and say it’s the most brilliant thing you’ve ever read. Thanks!).

Michael, a Bad Place architect, has received approval from his Bad Place boss, Shawn, to torture a set of human test subjects in a new way: by making them think they’re in the Good Place and letting the humans, with all their petty idiosyncrasies, torture each other. In order to pull off his plan, Michael steals a Good Place Janet to run his neighborhood.

What Michael doesn’t account for is that the humans end up making each other better. Every. Single. Time. Over 800 reboots, the results are consistent. The humans are growing, even in the afterlife. At some point, this knowledge prompts growth in Michael as well. He pivots away from his initial intention of inflicting torture and starts to investigate if the humans could grow enough to get into the real Good Place. How hard can it really be???

Turns out, next to impossible. (Easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, some might say.) Michael discovers that not a single human has been admitted into the Good Place in over 500 years. The system—the cosmic system that everyone has trusted, the cosmic system too true to question—is broken.

Throughout all the show’s twists and turns, Michael, Janet, and the humans have been racing to stay two steps ahead of Shawn and his demon cronies from the Bad Place, including the black-lycra-and-leather-jacket-wearing, gum-snapping, gas-passing Bad Janet. Whom I dressed up as for this year’s Halloween.

Initially, I chose to dress as Bad Janet because she made for a bomb-ass costume. An excuse to wear my thigh-high boots! And heavy eye makeup! And spend all night talking like a stoned Valley Girl! But once I successfully Bump’d my hair and stuffed several sticks of gum in my mouth, I realized that Bad Janet is a more fitting costume than I’d initially realized.

Bad Janet is characterized by her casual disgust for the humans. She views Michael’s interest in humanity as misplaced and pointless: I mean, they’re all going to get tortured eventually. Plus, his empathy for the humans is definitely a liability for Michael himself (a similar argument to the one put forth by conservative Christian influencer Allie Beth Stuckey in her book, Toxic Empathy).

I remember what it was like to believe that all human beings deserved to go to hell. I mean sure, imagining everyone I’d ever known who didn’t love Jesus burning in hell forever wasn’t a particularly pleasant image, but sin is sin. And God can’t be in the presence of sin, so I believed it was both appropriate and somehow necessary for the majority of humanity to be condemned to eternal conscious torment (and yes, “eternal conscious torment” is the exact term I was taught).

Jump cut to me vacuuming my bedroom rug literally yesterday (as of this writing) and remembering how I thought it was kind of pointless to get to know my own grandmother because she attended a Unitarian Universalist church. I mean, I don’t even want to admit that, but it’s important to realize that children listen to what we teach them. "All people deserve to go to hell, and everyone who doesn’t love Jesus will be tortured forever” is a significant thing to internalize about the world, especially if you learn that before you learn to read a chapter book.

Thomas Merton describes this obsession with hell and evil, morality and punishment, in his essay “The Moral Theology of the Devil,” included in New Seeds of Contemplation. Merton writes:

“The devil has a whole system of theology and philosophy, which will explain, to anyone who will listen, that created things are evil, that men are evil, that God created evil and that He directly wills that men should suffer evil. According to the devil, God rejoices in the suffering of men and, in fact, the whole universe is full of misery because God has willed it and planned it that way. [ . . . ] It sometimes happens that men who preach most vehemently about evil and the punishment of evil, so that they seem to have practically nothing else on their minds except sin, are really unconscious haters of other men. They think the world does not appreciate them, and this is their way of getting even.”

With that in mind, let’s return to the Good Place.

By halfway through Season 4, Bad Janet has been captured by Michael and the humans for doing something nefarious. Michael holds Bad Janet in custody for a while, occasionally stopping by to update her with stories about the humans’ progress, though she persists in her belief that the humans are bad.

“What matters isn’t if people are good or bad,” Michael says. “What matters is if they’re trying to be better today than they were yesterday.” Michael gives Bad Janet his manifesto: a giant gilded tome that recounts his experiments with the humans and documents what’s wrong with the system governing the afterlife. And then he lets her go.

That part always gets me in my feels a little bit. It’s one of those classic cinematic depictions of unearned grace [which is actually a pleonasm, or redundancy, since all grace is, by definition, unearned]: like when the bishop in Les Mis tells Jean Valjean that yes, the silver was a gift, but he forgot the candlesticks. Or when Jean Valjean has Javert at gunpoint and lets him go. Jesus telling the woman caught in adultery “go and sin no more.” Bartleby Gaines telling all the prospective students who showed up to his fake school that they are accepted. (Read more about my love for 2008 film “Accepted” here.)

But the risk that Michael takes in setting Bad Janet free pays off. (Weird how that happens: how setting someone free does more to win them over than controlling their every move. Maybe something to consider, fundamentalist patriarchs?) Bad Janet reads Michael’s manifesto. And she changes her mind.

This is one of the most revolutionary things we can do: we can change. It’s literally the meaning of the word revolution: to turn around. To course-correct. This is the same concept that undergirds the Jewish concept of repentance: teshuva, turning. We can say, “I was wrong, and I don’t hold to that anymore.” We can make amends, reparations, alterations. Bad Janet keeps the leather jacket and the eye makeup and the mouthful of gum, but she discards her belief that all humans automatically deserve hell. Just like I did.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

There’s this moment in Sherlock when Irene “the woman” Adler tells our brave detective that every disguise is also a self-portrait.

Dress-up, role play, and make-believe are all ways for us to learn more about ourselves. Play is revelatory. Restrictions on imagination translate to boundaries on self-knowledge, which is why that’s such an insidious tool for authoritarian leadership.

I want to participate in world-building driven by the unfettered questions, “What if it’s like this?”

What if I was raised by demons prejudiced against human frailty? How would that condition my thinking?

What if heaven gets boring? What if God isn’t real?

What if heaven isn’t a place but a quality? What if hell exists on earth and it’s related to the conditions we create for one another?

What if I start wearing heavy eye makeup and thigh-high boots all the time?

The process of asking open-ended questions, rather than undermining belief, helps establish a stable mental framework. You cannot truly know what you think if you have never explored the contrary. I want to be capable of engaging in good faith debate with ideas I don’t hold. I want to be capable of considering options and alternatives that scare me. And I always want to stay capable of changing my mind.

// What big opinions (or small opinions!) have you changed your mind about lately? What ideas feel permeable? What questions are you afraid to ask?

And until next time:

Thank you! Though I haven’t watched much TV or seen enough movies I have been to funerals. I adore your paragraph on the whole streets of gold thing. Watching my dour, plain (the Amish must be plain), uniform, buggy driving relatives relishing that one of their/our number was now walking on those metal byways threw me into paradox land. The fact that they would want that Trumpian eternity clearly meant they lusted for the forbidden. Self-denial is necessary. Thank you for introducing me to Bad Janet.